Adventures in Strange Lands Part II : Meteor Reflections

The plane from Goose Bay, Labrador slowly drops into the narrow crack , thousand foot cliffs on either side, no sign of an airfield anywhere, nothing but the glacier dead ahead. Greenland—-the world’s largest ice cube! It’s two miles thick in the center! Then, suddenly, a sharp turn and “Plonk”—we immediately touch down. Engines roar as the propellers reverse pitch. We stop with a few inches of runway to spare before we would become a shiny aluminum cross on the glacier. The Air Force sergeant stands and announces:

The plane from Goose Bay, Labrador slowly drops into the narrow crack , thousand foot cliffs on either side, no sign of an airfield anywhere, nothing but the glacier dead ahead. Greenland—-the world’s largest ice cube! It’s two miles thick in the center! Then, suddenly, a sharp turn and “Plonk”—we immediately touch down. Engines roar as the propellers reverse pitch. We stop with a few inches of runway to spare before we would become a shiny aluminum cross on the glacier. The Air Force sergeant stands and announces:

“Welcome to Sondre Stromfjord.” My inner thought is “What did I do to deserve this?”

A few months ago, in the spring of 1954, I was working at Baird Associates in Cambridge Mass. I got a phone call from Jim Hollis, an engineer of a strange radio communications company called Page, Creutz, Garrison, and Waldschmitt, actually a partnership, in Wash. DC. Later it became known as Page Engineers Inc. He said that I should meet him at Logan airport for a job interview, where he was changing planes in an hour. We met.

We chatted about this and that. Then he asked me “What is the power gain of a grounded grid radio frequency power amplifier?” I immediately answered “Mu plus one?” (Mu is the Greek letter for the tube voltage amplification factor. I knew the answer because I had built my ham radio power amp in Brooklyn using the grounded grid configuration.) Jim’s reply was “When can you start work?” That ended the interview. I reported to Page in Washington DC in June of 1954. Very soon I was on my way up north: Presque Isle and Limestone Maine, Goose Bay and Northwest River in Labrador, Narsarsuak and Sondre Stromfjord in Greenland. Page also had a large facility in Thule Greenland, but I never got to go there.

Jim Hollis had hired me to be a test engineer on a new communications system that Page was building from the U.S. to England. At that time the U.S. and the Soviet Union were at a standoff, each threatening the other with nuclear bombs carried by aircraft. Our Strategic Air Command developed the strategy of keeping our bombers in the air all day and night just waiting for the command to attack. But, up until the last moment, when the bombers were over the Soviet Union, we needed to be able to cut off the attack and bring the planes home if it was a false alarm. Therefore, we built a string of Air Force sites, all connected by short wave radio, from Washington DC to Maine (by ATT lines) and then up across Greenland over Iceland and down to the British Isles. Well, as it turned out radio propagation is kind of chancy in the arctic. Sometimes the aircraft could talk to Washington DC loud and clear and at other times there was dead silence as HF radio propagation died.

The new mode of communications that Page was developing was known as Ionospheric Forward Scatter. Imagine shining a flashlight up on the bottom of a cloud some 10,000 feet up and fifty miles away. With a very bright light you could see the light illuminate the cloud bottom, but also another person fifty miles on the other side of the cloud could see it too. The light was scattered in all directions by the cloud, but especially in the forward direction. So here you have connected two people a hundred miles apart with nothing but a (very bright) flashlight and a (fortuitously placed) cloud. Now replace the cloud with the E layer of the ionosphere which covers the entire earth some fifty miles up and replace the flashlight with a powerful broadcast transmitter (40 kilowatts) and a beam antenna which boosts the transmitter output by a factor of 100 and you have a communications link of a thousand miles or so that never goes off.

The new mode of communications that Page was developing was known as Ionospheric Forward Scatter. Imagine shining a flashlight up on the bottom of a cloud some 10,000 feet up and fifty miles away. With a very bright light you could see the light illuminate the cloud bottom, but also another person fifty miles on the other side of the cloud could see it too. The light was scattered in all directions by the cloud, but especially in the forward direction. So here you have connected two people a hundred miles apart with nothing but a (very bright) flashlight and a (fortuitously placed) cloud. Now replace the cloud with the E layer of the ionosphere which covers the entire earth some fifty miles up and replace the flashlight with a powerful broadcast transmitter (40 kilowatts) and a beam antenna which boosts the transmitter output by a factor of 100 and you have a communications link of a thousand miles or so that never goes off.

Page had two sites at Sondre Stromfjord, one for all the receiving antennas and equipment and the other for all the transmitters and their antennas. They were very far apart so as to minimize overload of the sensitive receivers by the powerful transmitter signals. Air Force personnel operated each site but Page engineers, such as myself, worked at both sites doing equipment maintenance and making tests for the engineers back in Washington DC. The transmitters were old FM broadcast transmitters in the 42 to 50 mHz band which became obsolete when the FCC in 1945 changed the FM band to the present 88 to 108 mHz. The receivers were hand made at Lincoln Labs, an offshoot of MIT. These receivers were super sensitive and low noise. As I recall, the transmitter site was at Lake Ferguson a few miles north of the air base and the receive site about 10 miles south of the base overlooking the fjord.

Initially I was at the transmitter site, learning the quirks of a 40,000 watt transmitter on 32 mHz. Our target was Thule Greenland, almost a thousand miles to the north. The antenna was a huge corner reflector some 60 ft high and almost 100 ft long placed right at the water’s edge so that the reflection off the lake’s surface added to the main radiation. Then, I was sent to the receive site, some 10 miles or so down the fjord. Here we were receiving the faint scatter signal from Goose Bay Labrador. “Here, listen to this!” the Airman said, and he turned up the volume on a small monitor loudspeaker.

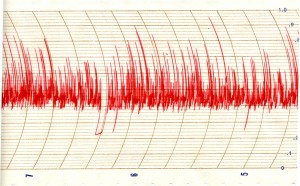

Well, I had never thought to listen to a teletype signal. It was just Mark and Space pulses of DC! He turned up the volume and I heard the familiar “Thump, Thump Thump ….” of the DC pulses. That and the faint background noise of the Lincoln receivers. Then suddenly “YYEEEEYYOWWW THUMP, THUMP” I jumped a foot high as the Airman laughed at my reaction.

Again, “YYEEEEYYOWWW THUMP ……” [Listen Here]

Not as long, maybe only 2 seconds, but slightly higher pitched. Then it slowly dawned on me “Doppler Shift” Something moving very fast was reflecting the Goose Bay signal and mixing with the scatter ray. An airplane? No. A missile? Hope not. I did a quick, rough calculation. It was moving toward us at about 70,000 miles per hour and going to zero in about 2 to 3 seconds. Then it came to me: “meteors!!!” I smiled with him as he explained to me that today was just a dull day and I should hear the “Whistles” when they were really active.

So now picture this:

I am above the Arctic Circle, listening to a radio signal from 500 miles away, ignoring what the radio signal is saying and absolutely fascinated by whistles from tiny specs of matter as they enter our atmosphere and become part of Earth.

Read more about Ionoscatter in this piece by Palle Preben-Hansen, OZ1RH

Did you enjoy this post? Why not leave a comment below and continue the conversation, or subscribe to my feed and get articles like this delivered automatically to your feed reader.

Comments

Hello Mark,

Google found you had referenced my paper on ionoscatter. Your writing is the first that confirms that there indeed was a ionoscatter station at Sønder Strømfjord (now Kangerlussaq), thanks a lot. The later DYE troposcatter link from about 1958 is much more well known.

73, Palle, OZ1RH

http://www.oz1rh.com

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Thank you for the wonderful post! Your daughter, Kim, suggested that I take a look at it as it connects to a scene in the children’s novel I’m working on. How incredible that meteors whistle! I love the idea of you listening to them like that.

You explained the science aspects very clearly, too; clearly enough for this non-techie to follow, at least. 🙂 The part about shining a flashlight up onto a cloud helped a lot.

Thank you for sharing your story!