Morse Code: The original “texting”

Samuel F.B. Morse

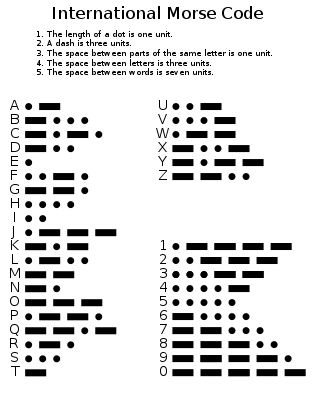

Morse code is a very strange type of communications. At first glance it appears as simply a substitution of dots and dashes for the letters of the alphabet. But then, as you get into it, Morse reveals all the twists and side tracks and inconsistencies of any foreign language. And, let me tell you from my own experience, if you don’t use it — you lose it! Just like any other foreign language.

International Morse evolved from the old railroad telegraph code now called American Morse. This was an extremely awkward code using simple instruments to give clicks and clacks at the beginning and ends of each dot and dash. But Samuel F. B. Morse and Alfred Vail made up for these deficiencies by using the very shortest sequences of dots and dashes for the letters most frequently found in English. So the letter E became one dot and the infrequent letter Q ended up as dash dash dot dash, and so on. This strategy turned out to be extremely efficient. It was fast and sort of self correcting. If a crash of static wiped out reception of a letter or two, and if you knew it was in English, then you could often guess from what you did hear and your knowledge of the English language just what had been messed up.

All this works very well so long as you are using English as the basic language. But as you try to use Morse to communicate in, say, Spanish the letter frequencies changed somewhat from English, and in Russian they changed a lot, “O” being significantly more frequent than “E”. Thus Morse is slightly less optimum for some foreign languages.

The ideographs of Chinese are impossible to transcribe directly into Morse code characters. Instead, each Chinese character is translated into a four digit number (or a three letter code) which is then sent in Morse code to the recipient. The Chinese phrase meaning “Information in Chinese” is 0022 2429 0207 1873 which can be transmitted using Morse code but must be looked up in a codebook or memorized to find out what the numbers mean. Fortunately in ham radio most hams use English. And they use a very restricted vocabulary of English mixed with a lot of abbreviations and shorthand character groups.

One interesting result of the impact of Morse on Chinese is that the four digit numbers above provide a common link between the different spoken Chinese words and their common Chinese character. This is especially important with Chinese names which vary greatly in speech for the same written character. A man named Hsiao Ai-Kuo in Taiwan is named Xiao Ai-Guo on mainland China and Siu Oi-Kwok in Hong Kong. All three names are written exactly the same with the Chinese Telegraph Code numbers 5618/ 1947/0948 for the corresponding Chinese character.

Early on, Morse communications took on the characters used by the older land-line telegraphers and added their own. So now we have 73 = Best regards, 88 = love and kisses, GE = good evening, PSE = please, TU = thank you, and some hundred or more expressions. Also the ship and shore stations developed a set of Q signals to speed up their message handling. QRA? means “What is the name of your station.” And, QTH? Means “What is your location?”. Without the question mark, QTH means “My location is _____ .” Most hams know about a dozen or two of the 60 odd Q signals in common use.

A typical transmission by a ham in Morse might be:

“de k3ee r george rst 5nn nm hr mark qth oakland md wx cold rain bt bt qsl? for dxcc tu vp6t de k3ee kn”

Meaning:

“This is k3ee, George. Your transmission received OK. Your signal is Readability 5, Strength 9, Tone 9. Name here is Mark. Located in Oakland Maryland. The weather here is cold rain. (pause) Can you send me a QSL card confirming my contact with you, for my DXCC award? Thank you. Vp6t from k3ee over to you, no one else.”

Now there are plusses and minuses in this Morse shorthand. It certainly is more compact than the longhand, about one third as long. And, 599 is a very common signal report. If one of the numbers is hit by a burst of static – so what? On the other hand, if a burst of noise took out the md for Maryland he might be confused as to just what state I am in. Notice also that the frequency of the letter E is way down. Thus, the receiving operator cannot just assume that a missing letter is most likely an E.

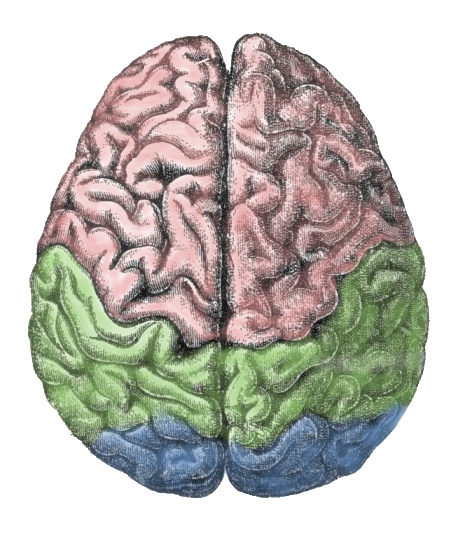

Some many years ago I hosted a conference on the potential for using computers to decode Morse and speech. One speaker, from the Army Signal Corps, described their 2 decade long search for an automatic Morse translator. Oh, their machines worked OK on strong, clear signals but add a little noise or interference and you got out garbage. All this time the human operator copied everything 599.

Then the IBM rep spoke. His problem was building a computer into which the president of a company could speak and get out a printed copy to hand to his secretary to clean up and send. His machine didn’t work very well either – but he knew the reason why. To translate a message, or word, into another language, in the presence of noise, you need to know all the words in both languages, and their relationships and their meanings together and their probability in the message. His computer memory was too small and his computer speed was to slow – but he knew of one machine that could do the job real well. That was the human brain!

Did you enjoy this post? Why not leave a comment below and continue the conversation, or subscribe to my feed and get articles like this delivered automatically to your feed reader.

Comments

No comments yet.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.